A geological contradiction to the Eastern Seaboard's otherwise flat Coastal Plain, the Cliffs rise in places to as much as 40 meters. They are cut into actively eroding, unconsolidated sandy, silty and clayey sediments of the lowermost portion of the Chesapeake Group. Throughout much of the Miocene, the region was the site of a shallow, inland arm of the temperate Atlantic Ocean during climatic cooling, uplift of the Atlantic Coastal Plain and eustatic changes in sea level. The stratal package preserves the best available record of middle Miocene marine and, less frequently, terrestrial life along the East Coast of North America.

WHO WAS CALVERT AND WHERE ARE WE?

The recorded history of the Chesapeake region is as varied as the geology, which began with the Spanish. The cartographer Diego Gutierrez recorded the Chesapeake on a map, calling it “Bahia de Santa Maria.” The English arrived with John White in 1585 and again in 1608 with John Smith’s entry onto the Calvert Peninsula. His mission was to explore the Chesapeake region, find riches, and locate a navigable route to the Pacific, all the while making maps and claiming land for England. On John Smith’s 1606 map (below), the Calvert Cliffs were originally called “Rickard’s Cliffes”, after his mother’s family name.

The first English settlement in Southern Maryland dates to somewhere between 1637 and 1642, although the county was actually organized in 1654. Established by Cecelius Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, English gentry were the first settlers, followed by Puritans, Huguenots, Quakers, and Scots. In 1695, Calvert County was partitioned into St. Mary's, Charles, and Prince George's, and its boundaries became substantially what they are today. Statehood wasn’t granted to Maryland until 1788. The Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Civil War waged in the region. In fact, the peninsula was the training site for Navy and Marine detachments, and the invasion of Normandy was simulated on the lower Cliffs of Calvert.

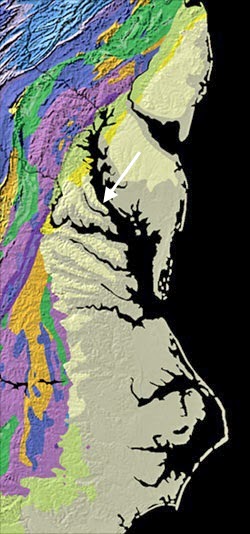

The Cliffs of Calvert reside on the broad, flat, seaward-sloping landform of the Coastal Plain of Maryland on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Calvert and southernmost Anne Arundel Counties. Located on finger-like Calvert Peninsula, the Cliffs are on the higher western section of the Plain, while the lower section, known as the Eastern Shore (always capitalized), is a flat-lying tidal stream-dissected plain, generally less than 60 feet above sea level.

|

| Red arrow indicates the region of Calvert Cliffs on the Atlantic Coastal Plain of the eastern shore of the Calvert Peninsula within the Chesapeake Bay. Modified from USGS map |

Chesapeake Bay is an estuary - the largest of 130 in the United States - with a mix of freshwater from the Appalachians and brackish water from its tidal connection to the Atlantic Ocean. The Bay's central axis formed by the drowning of the ancestral Susquehanna River by the sea that flowed to the Atlantic from the north during the last glacial maximum of the Pleistocene Ice Age some 20,000 years ago - when the planet's water was bound up in ice and global seas were lower.

Multiple advances of the Laurentide Ice Sheet blanketed Canada and a large portion of northern United States during Quaternary glacial epochs. Its advance never reached the region of Chesapeake Bay, having extended to about 38 degrees latitude. Being in a contemporary interglacial period - the Holocene - global seas are higher, but not at the level during the deposition of the Chesapeake Group at Calvert Cliffs during the Miocene.

During the time of deposition of the Calvert Cliffs, fluctuating seas drowned portions of southern Maryland. A shallow, protected basin of the Atlantic Ocean called the Salisbury Embayment was located in Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and southern New Jersey. It was one of many depocenters along the Eastern Seaboard, separated by adjoining highs or arches. The Salisbury Embayment structurally represents a westward extension of the Baltimore Canyon Trough that extends into the central Atlantic on the continent's shelf and slope.

The depositional history and relief of the Cliffs of Calvert are testimony to the elevated level of the seas in the Miocene. In addition, the Embayment resides on the “passive” margin of North America’s east coast, which is typified by subsidence and sedimentation rather than seismic faulting and volcanic activity found on the continent’s “active” west margin. The Embayment was and is in a constant dynamic state - passive but far from inactive.

How did the passive margin and the Coastal Plain of Maryland form geologically? What is the sediment source of the depocenters? What fauna occupied the ecosystem of Calvert Cliffs? These questions can't be adequately addressed without gaining an appreciation for the geological evolution of North America's East Coast. Here's a brief synopsis.

THE GEOLOGIC PROCESSES THAT SHAPED THE EASTERN COAST OF NORTH AMERICA

The supercontinent of Rodinia fully assembled with the termination of the Grenville orogeny in the Late Proterozoic and brought the world's landmasses into unification. Rodinia's tectonic disassembly in the latest Proterozoic gave birth to the Panthalassic, Iapetus and Rheic Oceans, amongst others. Rodinia's fragmentation was followed by the supercontinent of Pangaea's reassembly from previously drifted continental fragments throughout the Paleozoic.

A succession of orogenic events...

Using modern co-ordinates, the east coast of Laurentia (the ancestral, cratonic core of North America) experienced a succession of three major tectonic collisions during Pangaea's assembly – the Taconic (Ordovician-Silurian), Acadian (Devonian-Mississippian) and Alleghanian (Mississippian-Permian) orogenies. Each orogen built a chain of mountains that overprinted those of the previous event - closed intervening seas and added crust to the growing mass of the continent of North America.

A final orogeny assembles Pangaea...

The penultimate Alleghanian orogeny between Laurussia (Laurentia, Baltica and Eurasia) and the northwest Africa portion of Gondwana - the two largest megacontinental siblings of Rodinia's break-up - culminated with the late Paleozoic formation of Pangaea. That unification event constructed the Central Pangaean Mountains - a Himalayan-scale, elongate orogenic belt some 6,000 km in length within Pangaea at the site of continental convergence. Calvert Cliffs (red dot) had not yet evolved, but its deep Grenville basement was in place along with the orogen that would eventually blanket its coastal seascape with sediments from the highlands.

Supercontinental fragmentation...

Beginning in the Late Triassic, Pangaea’s break-up created a new ocean – the Atlantic – and fragmented the Pangaean range. As a result, the Appalachian chain remained along the passive eastern seaboard of the newly formed continent of North America from Newfoundland to Alabama, while severed portions of the range were sent adrift on rifted continental siblings. A supercontinental tectonic cycle is apparent between Grenville formation of Rodinia and its fragmentation and Alleghanian formation of Pangaea and its dissassembly.

The orogen's remnants form the Anti-Atlas Mountains in western Africa, the Caledonides in Greenland and northern Europe, the Variscan-Hercynian system in central Europe and central Asia, the Ouachita-Marathons in south-central North America, the Cordillera Oriental in Mexico, and the Venezuelan Andes in northwestern South America. As a result of Pangaea's fragmentation, the region of the future Calvert Cliffs (red dot) was finally positioned in proximity to the sea, awaiting the orogen to erode and Cenozoic eustasy to flood the landscape and deposit the Chesapeake Group during the Miocene.

North America's new passive margin...

By the Cretaceous, the Appalachian highlands had eroded to a nearly flat peneplain, sending voluminous fluvial sediments to the continental margin and shelf in a seaward-thickening wedge. Under the weight and the effect of lithospheric cooling, the passive marginal shelf began to subside and angle seaward as global warming and rising seas drowned both the coast and cratonic core of North America. The Salisbury Embayment, along with others up and down the coast in a scalloped array, was created by the tilting and reactivation of normal faults that extended westward to the Appalachian foothills. Initially, the regional dip was to the northeast, but Neogene uplift left the Coastal Plain's beds dipping to the southeast.

Subsidence and sedimentation...

Although classified as a passive continental margin, the "active" shelf received nonmarine

deposition through most of the Cretaceous. With the exception of the Oligocene, the Tertiary saw wave after wave of marine deposition on Maryland's subsiding shore spurned by rising global seas. During the Late Oligocene, Miocene and early Pliocene, the Chesapeake Group was deposited. The Group's lower three stratal components are exposed as wave-eroded bluffs at Calvert Cliffs. Their ~70 m of strata preserve nearly 10 million years of elapsed time. It forms the most available sequence of exposed Miocene marine sediments along the East Coast of North America.

The Chesapeake Group's Cliffs of Calvert...

Vacillating seas consequent to Pleistocene glaciation-deglaciation periodically flooded and exposed the land, backflooding rivers and bays such as the Chesapeake. Our present interglacial epoch - the Holocene - has re-exposed the Chesapeake Group and the Cliffs of Calvert to erosion. In spite of not having experienced a significant phase of tectonic convergence for over 200 million years, the modern Appalachian Mountains have been rejuvenated during the late Cenozoic, possibly isostatically in response to ongoing erosion or by mantle forcing. That contributed to river incision and deposition across the Coastal Plain with sedimentation such as the Chesapeake Group.

|

| A glowing Maryland sunrise illuminates the strata of the Calvert Cliffs looking south. Photo Courtesy of Stephen J. Godfrey, Ph.D., Curator of Paleontology, Calvert Marine Museum |

THE MID-EAST COAST'S PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES

North America's most easterly geomorphologic region is the siliciclastic sedimentary wedge of the Atlantic Coastal Plain that began to form with the breakup of Pangaea. It’s a low relief, gentle sloped, seaward-dipping mass of unconsolidated sediment over 15,000 feet thick, deposited on the margin of North America Appalachian-derived rivers and streams, and spread back and forth by the migrating shorelines of vacillating seas throughout the Cenozoic. In Maryland, progressing to the northwest from the Coastal Plain, one encounters the Piedmont Plateau at the Fall Line, the Blue Ridge, the Valley and Ridge and the Appalachian Plateau Provinces.

The five physiographic provinces are a series of belts with a characteristic topography, geomorphology and specific subsurface structural element. The overall trend is from southwest to northeast along the eastern margin of North America. Their strike and geologic character have everything to do with the tectonic collisions that built mountains, recorded periods of quiescence, formed and fragmented at least two supercontinents, and opened and closed the oceans caught in between.

|

| Location of Calvert Cliffs on the Chesapeake Bay's western shore of the Atlantic Coastal Plain (light colored) Modified from USGS map |

Calvert Cliffs is on the Chesapeake Bay's western shore of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, as are the major cities on the mid-east coast - Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, Washington, etc. If you connect them on a map, you'll locate the approximate western boundary of the Coastal Plain called the Fall Line or Zone. It's the geomorphic break (and geographic obstacle) where a 900-mile long escarpment of falls and rapids separates the Coastal Plain from hard, metamorphosed crystalline rock of the Piedmont foothills to the west.

The Piedmont and Blue Ridge share similar types of crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks of the core of the Appalachians. The majority of Blue Ridge rocks are related to events of the Precambrian and Cambrian from Grenville mountain building to the Cambrian rift basins, while most of the Piedmont rocks were transported and accreted to North America. A discussion of the details of tectonic derivation and geologic structure of the remaining westerly provinces is beyond the scope of this post.

MIOCENE STRATIGRAPHY OF CALVERT CLIFFS

The Calvert Cliffs consist largely of relatively undeformed and unlithified strata of silts, sands and clays of the Calvert, Choptank and St. Mary's formations (Shattuck, 1904) in ascending order of the Chesapeake Group. The formations are interrupted by a series of erosional unconformities and other hiatal intervals and preserve nearly 10 million years of elapsed time.

The Miocene succession was deposited as a complex package representing a first-order transgressive-regressive cycle with numerous superimposed smaller-scale perturbations of sea level. Overall, the record is one of gradual shallowing within the Salisbury Embayment and is reflected in the character of the strata that progresses from inner to middle shelf to tidally-influenced, lower-salinity coastal embayments. Deposition occurred under subtropical and warm temperate conditions in a shallow marine shelf environment at a maximum water depth of more than ~40-50 meters.

The exposures include not only the Calvert Cliffs but the Westmoreland and Nomini Cliffs along the Virginia Shore of the Potomac River. Debated for more than a century, estimates for the basal Calvert range from early Early Miocene to mid-Middle Miocene.

RECESSION OF THE COASTAL BLUFFS

A general absence of beaches below the cliffs is a characteristic of the region. Direct wave undercutting at the cliff-toe, freeze-thaw erosion, underground seepage at sand-clay interfaces and mass-wasting (the average inclination is 70 degrees) are accompanied by rapid wave removal of colluvium (slope debris). Long-term rates can exceed 1 m/yr. Slumps, rotational slides and fallen trees are constantly being generated and removed. For these reasons, beachcombing for fossils and excavating the cliff-toes is a dangerous and prohibited venture. Collected is allowed in designated parks along the shoreline such as Calvert Cliffs State Park, Flag Ponds Nature Park and Brownies Beach, and private beaches given the owner's permission.

Two vying factions in regards to the Cliffs are scientists that reap the benefit of ongoing erosion and the homeowners, who seek real estate in close proximity to the cliff edge for the sake of a bay view. For the former, the best way to preserve the Cliffs is to let them erode naturally, while the latter would like to riprap (with stone or concrete), bulkhead, sandbag and groin-field the Cliffs to preserve them and their property. In dealing with Mother Nature, in this regard, shoreline protection reduces the risk of cliff failure, although it doesn't eliminate it. It's only a matter of geologic time.

To reach otherwise inaccessible sections of the Cliffs and lessen the inherent dangers of collapse and burial, this mode of exploration employs descent from above. Excavation into the unlithified substrate is facilitated by an air-powered drill using a scuba tank's compressed air.

|

| From Google Science Fair 2014. See the video here. |

THE CLIFF'S FOSSILIFEROUS BOUNTY

The formations preserve more than 600 largely marine species that include diatoms, dinoflagellates, foraminiferans, sponges, corals, polychaete worms, mollusks, ostracods, decapods, crustaceans, barnacles, brachiopods and echinoderms. The macrobenthic fauna (large organisms living on or in the sea bottom) act as good indicators of salinity. The Calvert and Choptank are dominated by diverse assemblages of stenohaline organisms (tolerating a narrow range of salinity); whereas, the younger St. Mary's Formation exhibits an increasing prevalence of euryhaline molluscan assemblages (tolerating a wide range of salinity). The changes within the assemblages reflect the fluctuating freshwater conditions within the Salisbury Embayment.

Vertebrate taxa include sharks and rays, actinopterygian fish, turtles, crocodiles, pelagic (open sea) birds, seals, sea cows, odontocetes and mysticetes (whales, porpoises and dolphins).

In addition, the Cliffs preserve isolated and fragmentary remains of large terrestrial mammals (peccaries, rhinos, antelope, camels, horses and an extinct group of elephants called gomphotheres), palynomorphs (pollens and spores), and even land plants (from cypress and pine to oak) that bordered the Miocene Atlantic Coast and were carried to the sea by floodplains, rivers and streams sourced by the Appalachians.

|

| Miocene River Environment by Karen Carr with permission |

SIFTING THE SURF FOR FOSSILS

Armed with a plastic garden rake in hand from the local hardware store, I collected this fossil potpourri (below) on a brief 60 minute stroll along the beach at Flag Ponds. Their abundance and availability is a testimony to the richness and diversity of the Miocene marine fauna. The fossils are continually being generated from the eroding cliffs and their underwater extensions.

I am uncertain as to the specific origin of the mammalian bony fragments, but I suspect they are largely from marine fauna (i.e. dolphin, whale, seal, etc.) rather than terrestrial, since the former vastly outnumber the latter. Cetaceans such as the whale have repurposed an air-adapted mammalian ear for the differentiation of underwater sounds. The shell-like otic tympanic bulla is a thickened portion of the temporal bone located below the middle ear complex of bones. The large dense bone is well preserved and can easily be mistaken for an eroded fragment of rock.

The crocodile tooth is an indication that rivers and swampy habitats existed in the marginal marine environment of Calvert Cliffs. Shark teeth are the most common vertebrate fossils preserved at the Cliffs. Their numbers are commentary on the favorable paleoenvironmental conditions that existed in the Salisbury Embayment. Of course, sharks continually produce and shed teeth throughout their lives, facilitated by the absence of a long, retentive root structure, and are composed of durable and insoluble biogenic apatite, which favors their preservation. Calvert Museum collections contain as many as 15 genera. The main constituents are Carcharhinus, Hemipristis, Galeocerdo, Isurus and Carchrius. Carcharhiniformes shed about 35,000 teeth in a lifetime!

Appearing in the fossil record about 395 million years ago (middle Devonian), the Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous skeletal fish) is divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii, which includes sharks, rays and skates, and Holocephali (chimaeras). Elasmobranchii are distinguished by their 5-7 pairs of gill clefts, rigid dorsal fin, presence or absence of an anal fin, placoid dermal scales, teeth arranged in series within the jaws and the upper jaw being not fused to the cranium. Along with a dolphin tooth and a few gastropods, here are a few specimens collected from the surf at Calvert Cliffs State Park, about five miles southeast of Flag Ponds.

From these small samples, one can glean the ancient habitat at Calvert Cliffs during the Miocene. The combined study of both fossils and rock layers are essential in reconstructing the paleo-geography of the Cliffs.

C. MEGALODON

By far, the largest and rarest shark teeth at Calvert Cliffs (but widely distributed within the world's oceans) are those of a "Megalodon," an extinct species of shark that lived from the late Oligocene to early Pleistocene (~28 to 1.5 million years ago). Its distinctive triangular, strongly serrated teeth are morphologically similar to those of a Great White shark (Carcharodon carcharias), a fact that fuels the debate over convergent dental evolution versus an ancestral relationship.

The controversy has resulted in a taxonomic name of either Carcharodon megalodon or Carcharocles megalodon - commonly abbreviated as C. megalodon. The “Meg” is regarded as one of the most powerful apex predators in vertebrate history. On rare occasion, extinct cetacean fossilized vertebrae have been uncovered with bite-marks suggestive of mega-tooth shark predation or scavenging. Megalodon is represented in the fossil record exclusively by teeth and vertebral centra, since cartilaginous skeleton is poorly preserved.

.jpg) |

| C. megalodon dining on cetaceans With permission from artist Karen Carr |

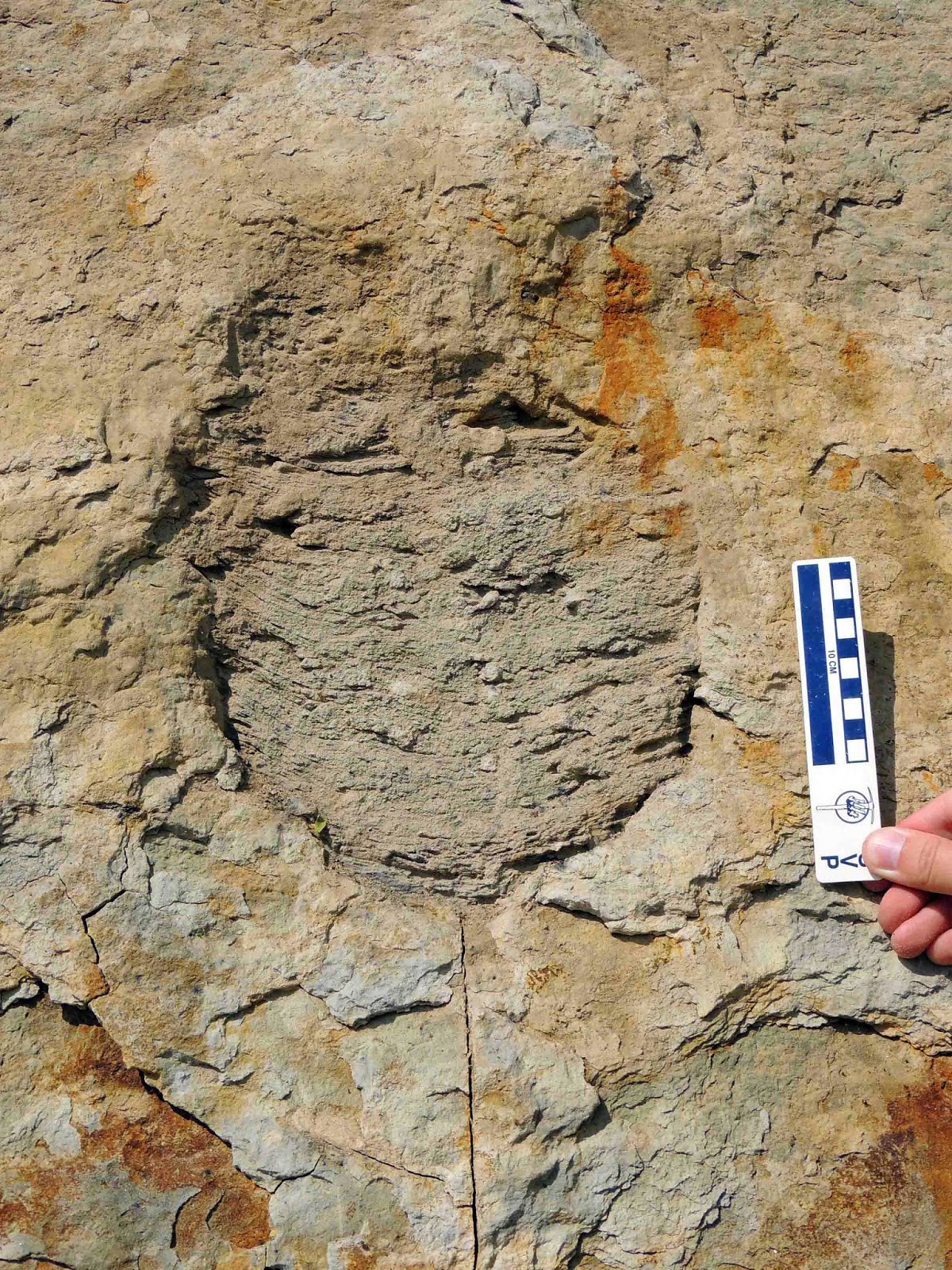

SKULLS AND BURROWS OF A NEW SPECIES

Dr. Stephen Godfrey of the Calvert Marine Museum has been conducting paleontological studies in the Calvert Cliffs for some 15 years. After rafting along the shoreline to the excavation site, this paleontologist is taking measurements of a trace fossil interpreted as an infilled tilefish burrow from the Plum Point Member of the Calvert Formation deposited some 16 million years ago. In a 2014 paper in the JVP (see reference below), well preserved, partially complete, largely cranial remains of tilefish are described. They have been collected over the past three decades from Miocene deposits outcropping in Maryland and Virginia.

|

| Ruler in hand, paleontologist W. Johns investigates the exposed tilefish burrow. Photo Courtesy of Stephen J. Godfrey, Ph.D., Curator of Paleontology, Calvert Marine Museum |

Lopholatilus ereborensis, a new species of family Malacanthidae and teleost (infraclass of advanced ray-finned fish), inhabited long funnel-shaped vertical burrows that it excavated for refuge within the cohesive bottoms of the outer continental shelf of the Salisbury Embayment that likely inhabited other parts of the warm, oxygenated waters of the western North Atlantic outer shelf and slope. The species name was derived from 'Erebor,' the fictional name for the Lonely Mountain in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit. Like the mountain-clan of dwarves, the tilefish mined the substrate.

COLONIAL SMOKING PIPE

In an attempt to see what fossilized remains might have filtered down from overlying Miocene and more recent strata, I walked the beach until finding a break where a wash had carved a trough through the bluffs. I immediately spotted a white object glistening in the sun in a stream bed filled with gravel and tiny sharks teeth that turned out to be the worn remnants of a Colonial-era smoking pipe.

Pipes of clay were first smoked in England after the introduction of tobacco from Virginia in the late 16th century. Sir Walter Raleigh, an English sea captain, was one of the first to promote this novel habit acquired from Native Americans that had practiced its ritual use for many centuries. By the mid-17th century clay pipe manufacture was well established with millions produced in England, mainland Europe, and the colonies of Maryland and Virginia. For various reasons, clay pipe demand declined by the 1930’s.

Clay pipes were very fragile and broke easily, and along with their popularity, they are commonly found at Maryland and Virginia colonial home sites. In Colonial-era taverns, clay pipes that were passed around were supposedly broken off at the stem for the next user in the interest of hygiene. Some clay pipes can be dated by the manufacturer's stamp located on the bowl, which was unfortunately missing in this lucky but well calculated find.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED REFERENCES

• Evolution of Equilibrium Slopes at Calvert Cliffs, Maryland by Inga Clark et at, Shore and Beach, 2014.

• Frequency of Effective Wave Activity and the Recession of Coastal Bluffs: Calvert Cliffs, Maryland by Peter R. Wilcock et al, Journal of Coastal Research, 1998.

• Geologic Evolution of the Eastern United States by Art Schultz and Ellen Compton-Gooding, Virginia Museum of Natural History, 1991.

• Maryland's Cliffs of Calvert: A Fossiliferous Record of Mid-Miocene Inner Shelf and Coastal Environments by Peter R. Vogt and Ralph Eshelman, G.S.A. Field Guide, Northeastern Section, 1987.

• Miocene Cetaceans of the Chesapeake Group by Michael D. Gottfried, Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History, 1994.

• Miocene Rejuvenation of Topographic Relief in the Southern Appalachians by Sean F. Gallen et al, GSA Today, February 2013.

• Molluscan Biostratigraphy of the Miocene, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain of North America by Lauck W. Ward, Virginia Museum of Natural History, 1992.

• Slope Evolution at Calvert Cliffs, Maryland by Martha Herzog, USGS.

• Stargazer (Teleostei, Uranoscopidae) Cranial Remains from the Miocene Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, U.S.A. by Giorgio Carnevale, Stephen J. Godfrey and Theodore W. Pietsch, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, November 2011.

• Stratigraphy of the Calvert, Choptank, and St. Mary's Formations (Miocene) in the Chesapeake Bay Area, Maryland and Virginia by Lauck W. Ward and George W. Andrews, Virginia Museum of Natural History, Memoir Number 9, 2008.

• The Ecphora Newsletter, September 2009.

• Tilefish (Teleostei, Malacanthidae) Remains from the Miocene Calvert Formation, Maryland and Virginia: Taxonomical and Paleoecological Remarks by Giorgio Carnevale and Stephen J. Godfrey, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, September 2014.

•Variation in Composition and Abundance of Miocene Shark Teeth from Calvert Cliffs, Maryland by Christy C. Visaggi and Stephen J. Godfrey, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, January 2010.

WITH GREAT APPRECIATION

I wish to express my gratitude and thanks to Stephen J. Godfrey, PhD., Curator of Paleontology of the Calvert Marine Museum, for providing valuable support (personal communications, October 2014), documentation and photographs of Calvert Cliffs and his recent excavation and publication.

GO VISIT!

Calvert Cliffs Marine Museum was founded in 1970 at the mouth of the Patuxent River in Solomons, Maryland. Visit them here, but do go there! You can join the museum here.

OR SUBSCRIBE!

The Ecphora is the quarterly newsletter of the Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club. Ecphora gardnerae gardnerae is an extinct, Oligocene to Pliocene, predatory gastropod and the Maryland State Fossil, whose first description appeared in paleontological writings as early as 1770. Sadly, riprapping (rock used to protect shorelines from erosion) has covered one of only two localities in the State of Maryland where the fossil can be found. The other is on private land and off limits without permission. Ironically, Marylanders can find their state fossil in Miocene strata of Virginia. Download copies of current and past newsletters here or simply subscribe.

.jpg)