For me, there’s nothing like “the wide, open spaces.” Perhaps it comes from growing up in Central New York State

This expansive vista looks down the long escarpment of the Straight Cliffs, the cliff-face of

Their mission was to establish a new settlement in the region of the San Juan River in southeastern

GETTING OUR BEARINGS

The Straight Cliffs rise 1,110 feet or more, and as their name implies, extend for 50 miles to the southeast. The cliffs form the eastern escarpment of

At the foot of the cliffs runs Fiftymile Bench, a platform or broad terrace with a line of smaller, lower cliffs of its own, and more well-developed in the southern reaches of the Straight Cliffs. At various intervals, a succession of cusps juts out from the long bench.

And below the bench, lies the sagebrush, blackbrush, rabbitbrush and cacti decorated desert through which we traveled. The area is remote, isolated and majestically beautiful.

A GEOLOGICAL BOUNDARY

The Straight Cliffs and

The uppermost diagram (below) shows the centrally-located, dissected-mesa of the Kaiparowits section of the GSENM, viewed from a northern perspective. Fiftymile Mountain and the Straight Cliffs (circled) form the natural boundary with the easternmost section of the monument, Escalante Canyons (lowermost diagram). The Escalante Canyons section is viewed from a southern perspective.

The Straight Cliffs are one of the boldest expressions of the Gray Cliffs of the Grand Staircase, the GSENM's westernmost section. The Staircase is a series of topographic benches and cliffs, and that, as its name implies, progressively steps up in elevation from south to north, from northern

THE REGIONAL GEOLOGY IS A REFLECTION OF THE TECTONIC BIG PICTURE

The relentless drought of the Early Jurassic that dominated the vicinity of the future Colorado Plateau brought the Wingate and Navajo wind-driven sand seas of the Glen Canyon Group to the region. Likewise in the Middle Jurassic, the Page and Entrada Sandstone eolian ergs inundated the region, but this time in association with the Sundance Sea, a narrow restricted arm of the ocean that entered from Wyoming into the subsidence space of the Utah-Idaho Trough, a foreland basin. The complex and varied deposits of the sea's fluctuating shoreline left the sediments of the San Rafael Group (such as the region's Carmel, Page and Entrada silt and sandstones).

During the Late Jurassic the region experienced the widespread, fluvially-generated Morrison Formation in the wake of the Nevadan Orogeny to the west, a mountain-building event that contributed to the formation of the Cordilleran Arc. Cordilleran Orogenesis in the western United States spanned at least 120 million years from the Middle Jurassic into early Eocene time. It comprised numerous mountain-building events that culminated with the formation of an enormous, elongate mountain range from Alaska to southern Mexico, with a complex and diverse stratigraphy.

Beginning in the latest Jurassic, the subduction of the oceanic Farallon Plate beneath the North American Plate along western North America resulted in the formation of the Sevier fold and thrust belt. Siliciclastic sediments were shed from the west carried by rivers into a seaway that formed in the immense, flooded foreland basin that developed in the center of the continent. During the Cretaceous, the Western Interior Seaway inundated most of the interior of North America including the GSENM area in southern Utah, leaving a vast array of sediments as its shoreline changed and sealevel rose and fell with deposits such as the region's Dakota Formation deposited in coastal areas ahead of the encroaching sea. The Tropic Shale represents muds deposited at the bottom of the sea. The Straight Cliffs, Wahweap and Kaiparowits Formations represent sediments that were deposited on a piedmont belt between the mountains and the sea, after the sea retreated to the east.

These events left their deposits after which Paleogene uplift and dissection painted the finishing touches on the canvas of the landscape. On the map below at about 85 Ma, note the location of the Sevier Highlands, its associated thrust fault, and the future landform of the Kaiparowits Plateau. The Straight Cliffs-Fiftymile Mountain boundary between it and the Escalante Canyons section to the east formed after Laramide uplift of the Colorado Plateau and the subsequent dissection of the region locally by tributaries of the Colorado River System into the deposits of the Glen Canyon Group.

THE REGIONAL GEOLOGY

THE CLIFFS

The northwest to southeast-trending Straight Cliffs looks somewhat like the east to west-trending Book Cliffs located further to the north, formed under similar depositional conditions and time frames. The former’s trend is roughly parallel and the latter’s trend is roughly perpendicular to the ancient shoreline of the Western Interior Seaway where they were deposited nearly 90 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous. The Straight Cliffs are composed of dark gray, massive marine shales interbedded with tan sandstones. They contain a diverse fluvial and marine architecture of offshore, shoreface, coastal plain, paludal and fluvial facies that reflect the transgressive-regressive whim of the seaway's fluctuations in sealevel. With the mind's eye staring at the Straight Cliffs, you can see layer after layer of ancient beaches and barrier islands formed by the shifting shoreline similar to the Atlantic Coast of today.

The majority of the cliffs are composed of the Straight Cliffs Formation's John Henry Member, a slope and ledge-former, representing thick beach sandstone beds separated by muddy sandstones deposited in a shoreline environment. The John Henry also contains thick, lagoonal coal deposits. Two members form the base of the cliffs, the Smoky Hollow Member (back-beach and lagoonal deposits) and resting on the Tibbett Canyon Member (offshore sandstones).

THE BENCH

Fiftymile Bench is built on the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation, much of which is covered by colluvium and landslide debris derived from the overlying Straight Cliffs Formation. Beneath the bench’s debris, windows of the underlying gray, muddy Tropic Shale and thin Dakota Formation are present. In places, Pleistocene-age, mass wasting deposits have cascaded over the bench’s lower cliffs and ledges in the Morrison Formation's Salt Wash Member to the desert-flats below. In one particular locale, seen from a distance, the erosional process of a flow is evident in the formation of hoodoos (below).

THE FLATS

The

This map of the GSENM illustrates the relationship of its three sections and the geological boundary that the Straight Cliffs and Fiftymile Mountain form between the Kaiparowits and Escalante sections. Also notice the Hole-in-the-Rock Road paralleling the strike of the cliffs from Escalante to the southeast towards the Colorado River and Lake Powell. The Kaiparowits Plateau is roofed with marine, fluvial and floodplain deposits; whereas, the Escalante Canyons have been unroofed of such until east of the Waterpocket Fold.

Here's a bedrock map at the Straight Cliffs-Fiftymile Mountain boundary zone. Note the Hole-in-the-Rock Road running from Escalante to Lake Powell.

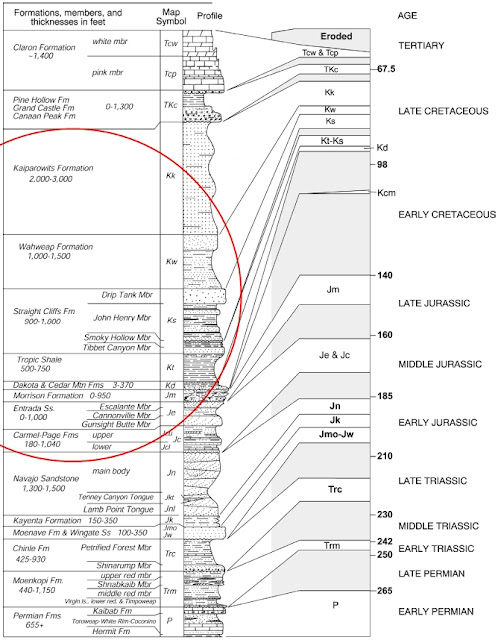

Stratigraphic column in the region of the Straight Cliffs (circled)

Having departed from the town of Escalante, we headed south on the Hole-in-the-Rock Road. This view looks back to the north toward Escalante with the Straight Cliffs located to the west. The photo was taken while literally standing on the Mormon's Hole-in-the Rock trail through the desert. Our SUV, off to the right, is parked on the Hole-in-the-Rock Road. After having been constructed over 130 years ago and having been used for only one year by Mormon pioneers, you can still see the swales created by the Conestoga wagon wheels through the red Carmel soil.

Continuing our journey south on the Hole-in-the-Rock Road for fifty miles or so, we turned off towards the cliffs and took a scenic detour on Fiftymile Bench Road. The road uses a landslide over Morrison cliffs to gain access onto Fiftymile Bench. Seen below, we ascended numerous switchbacks on a rugged road that led us to the top of the debris flow that came off the bench. The view of the desert flats far below (at about 4,300 feet above sea level) in the Carmel formation, and the Escalante Canyons and watershed of the Escalante River in the distance was quite spectacular.

Unbeknownst to us at the time, we were to make camp that night at Sooner Rocks, the barely visible, rocky outcrop in the center of the photo. The debris flow (at about 5,600 feet) on which we were ascending is comprised of an unconsolidated rocky mix largely from the Straight Cliffs above. You can spot the array of boulders in the foreground that have cascaded down from the cliffs and the road snaking upward from below. Also notice a cusp of the Fiftymile Bench extending off to the left in the Morrison Formation. About 50 miles away, the Henry Mountain laccolithic complex is faintly discernible at the horizon to the right (north-northeast) beyond the Waterpocket Fold, while Boulder Mountain capped in Tertiary lava flows is far to the left (north-northwest).

With sunset rapidly approaching and the wind picking up, we began an earnest search for a good spot for camp. Every desirable campsite with a sheltered wind-break seemed taken. Eventually we settled on Sooner Rocks for camp just off theHole-in-the-Rock Road , built of smooth, slick, red Entrada Sandstone in the form of a cluster of resistant, domed, bare-rock outcrops. At sundown the temps began to drop and the wind began to gust at 40 mph plus. We set up camp, staked and secured our tents, opened a fine bottle of wine and watched the sun set, while bracing for a storm at night that never really came.

Unbeknownst to us at the time, we were to make camp that night at Sooner Rocks, the barely visible, rocky outcrop in the center of the photo. The debris flow (at about 5,600 feet) on which we were ascending is comprised of an unconsolidated rocky mix largely from the Straight Cliffs above. You can spot the array of boulders in the foreground that have cascaded down from the cliffs and the road snaking upward from below. Also notice a cusp of the Fiftymile Bench extending off to the left in the Morrison Formation. About 50 miles away, the Henry Mountain laccolithic complex is faintly discernible at the horizon to the right (north-northeast) beyond the Waterpocket Fold, while Boulder Mountain capped in Tertiary lava flows is far to the left (north-northwest).

With sunset rapidly approaching and the wind picking up, we began an earnest search for a good spot for camp. Every desirable campsite with a sheltered wind-break seemed taken. Eventually we settled on Sooner Rocks for camp just off the

“Goodnight stars, goodnight air, goodnight noises everywhere.”

From Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown

In the morning, we awakened to a light rain and a spectacular cloud break at sunrise that ignited the Sooner Rocks in brilliant Entrada-orange. Like the Navajo Sandstone, the Entrada Sandstone exhibits large-scale eolian cross-bedding and weathers to smooth surfaces. Notice its swirly, undulating cross-beds which have been selectively etched-out by erosion. It reminded me of graded fields back home in the northeast that had been harvested of corn. Also, notice the criss-crossing, wavy and anastomosing, whitish network of deformation bands on the sandstone-dome. Probably of tectonic origin, they are indicative of accommodation to normal slip-movements, many exhibiting offsets. Their lighter, white color is likely attributable to variable bleaching through interaction with hydrocarbon-bearing solutions or other reducing agents, and indicative of the host sandstone's permeability early in its developmental history. Geochemical modeling implies the removal of some iron by fluids after chemical reduction, further contributing to their color.

As the rising sun illuminated the nearer bench portion of the escarpment to the west, we noticed a dusting of snow along the top of the Straight Cliffs, highly atypical for late May. Exquisite!

After investigating a few slot canyons in the area, we returned to the Hole-in-the-Rock Road and headed north, back to Escalante. This view nicely shows the banded stratigraphy of the Straight Cliffs, the Fiftymile Bench in the multi-colored Morrison Formation, and the heavily vegetated, Carmel desert on which we've been traveling.

“Now...Bring me that horizon" (Pirates of the Caribbean)

Highly Suggested Reading: Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments by the Utah Geological Association and Bryce Canyon Natural History Association, Second Edition, 2003.

Highly Suggested Reading: Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments by the Utah Geological Association and Bryce Canyon Natural History Association, Second Edition, 2003.

I have to say that this is one of the best laid out and informative blogs I have seen in a long time. I have seen several that post pictures of the rocks and thier formations, but not one that explains it all. So well done to you. Great Blog.

ReplyDeleteMy sincere appreciation goes out to Spiral Staircase for this comment! It's great to know that the work that you put into a post (let alone a blog) has been recognized and is of value. It's comments such as yours that "keep me going." Thank you, again! Jack

ReplyDeleteNo problem Dr Jack. I think you know yourself that this is a very well finished and complete blog, when so many others are much smaller in intellectual value. So I’m sure I and everyone else that reads this blog appreciate it.

ReplyDeleteThat's a lot of information on GSENM and beautiful pictures. I love to have this information on Escalante's Chamber of Commerce website. Keep on writing!

ReplyDelete